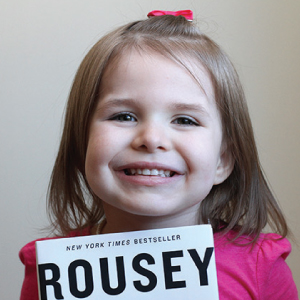

Two things will tell you when a certain vibrant 7-year- old is about to sprint full force toward the ball pit in Heartspring’s therapy gym. First, her eyes scream determination. Second, her smile beams with mischief. And before anyone can stop her, Braelynn is smack-dab in the middle of a colorful mess of plastic balls. And while her therapist works to get her back on task, Braelynn’s mom, Gentry, looks on from outside the hallway window.

Two things will tell you when a certain vibrant 7-year- old is about to sprint full force toward the ball pit in Heartspring’s therapy gym. First, her eyes scream determination. Second, her smile beams with mischief. And before anyone can stop her, Braelynn is smack-dab in the middle of a colorful mess of plastic balls. And while her therapist works to get her back on task, Braelynn’s mom, Gentry, looks on from outside the hallway window.

For Gentry, Braelynn’s boldness and energy isn’t something to take for granted, because there was a time when she didn’t know if Braelynn would even be able to walk.

Gentry and her husband, Matthew, became parents at a young age. At the time, Matthew was also on the verge of leaving for Navy boot camp. Seven months into the pregnancy, doctors noticed that their baby’s growth was behind. She seemed very small, especially her head size.

At birth, Braelynn weighed a mere three pounds and 14.5 ounces. Uncertain of why, doctors in the family’s hometown of Dodge City made the decision to fly her to Wichita’s Wesley Medical Center for tests.

“Then, we received news that no parent should ever have to hear. We were told that our daughter had no peaks and valleys in her brain—that she had Lissencephaly,” Gentry said.

According to the National Organization for Rare Disorders, Inc., Lissencephaly indicates an abnormally smooth brain. It is also characterized by a smaller head circumference. The doctor said she would never walk, talk or hear.

“My husband, with tears in his eyes, asked the doctor to give him one piece of hope. And the doctor said he couldn’t,” Gentry continued.

Shortly after Braelynn’s birth, Matthew left for the Navy. And Gentry faced a difficult, unclear road ahead.

One day, Braelynn’s grandfather came across a Lissencephaly conference in Indiana. While there, Gentry and 3-month-old Braelynn met a doctor who specializes in brain disorders. To their surprise, the doctor told them Braelynn actually had Microcephaly, which literally means “small head,” and is accompanied by developmental delays.

Instantly, the sense of hope they’d been longing for became a reality. While there was still much to overcome, the outlook for Braelynn suddenly looked significantly brighter.

After some respiratory issues, a Cystic Fibrosis scare, chronic ear infections and a high-risk for pneumonia, Braelynn progresses on her own time. Yet, the things doctors said she would never do washed away as she learned to crawl, walk and say the word “mama.”

After some respiratory issues, a Cystic Fibrosis scare, chronic ear infections and a high-risk for pneumonia, Braelynn progresses on her own time. Yet, the things doctors said she would never do washed away as she learned to crawl, walk and say the word “mama.”

However, another obstacle stood in this family’s way— the need for consistent therapies. With her father in the military, Braelynn’s family moved often. While it’s already difficult to find good programs, having to repeat the process made it even harder for Braelynn to reach her potential, and her therapies were limited to school hours.

“I always felt like Braelynn needed and deserved more... it made me feel like I wasn’t doing my job,” Gentry said.

In 2011, Matthew got stationed in Wichita. After settling Braelynn into a new school, Gentry and her sister came across Heartspring and scheduled therapy appointments.

After a year, Braelynn has progressed in many ways. Her previous frustrations with communication have been reduced since she’s learned new signs, more words and more ways to communicate. Many of the skills she needs to be independent have also improved. Braelynn can now feed herself, thread beads, draw lines, solve puzzles and hop! Her personality and pride are gleaming as a result.

“Heartspring has given us hope for Braelynn. I finally feel like she is where she needs to be...I feel like the possibilities are endless!” Gentry said.